Predictions of Swedish last name popularity

Last names - we all have one. Except if you are Icelandic. But I do not live in Iceland, I live in Sweden, where we do have last names. This post chronicles my little dive into the data behind Swedish last names, for fun and personal development. More specifically, this project uses historical data of the frequency of last names in Sweden to predict future occurrences.

Motivation

The main goal of this project was to familiarize myself with Jupyter notebooks (which I have found out that I think are great) and to get better at implementing machine learning in practice. One added benefit was getting to learn about quirks in the data behind last names in Sweden. Did you, for instance, know that most of the popular last names are on a downward trend? Yes, that’s right, pretty much all of them.

Data

The data was gathered from Statistiska centralbyrån (SCB), the Swedish statistics authority, using their database. The dataset contains information on the top 100 most used last names in Sweden between 1980 to 2019, measured yearly. Because of fluctuations in which last names make the top 100 cut each year there are a few more last names than just 100.

One annoying feature of the dataset is that it is very literal in that it is the top 100 last names. Any period of time where a last name dips out of the top 100, the number of occurrences of the last name is simply marked as zero. I mean, come on, you’re SCB, you must have the complete data ready to go. Just give me it.

For pre-processing purposes, I simply divided the data by the median number of occurrences in the dataset.

Execution

Data generator

One thing that I liked about this project is that I unexpectedly had the opportunity to write a data generator. There were two primary reasons that made me do so. Firstly, due to the limited available I wanted to artificially create more. Secondly, I wanted my network to handle inputs of different lengths well. Creating my own data generator allowed me to fulfill both requirements by randomizing window sizes and locations. Technically, this does not create more data, but it allows for a much wider range of unique inputs compared to having fixed window sizes. Generating on the fly was also necessary because it would not be feasible to keep a large number of subsets of the dataset in memory.

Training

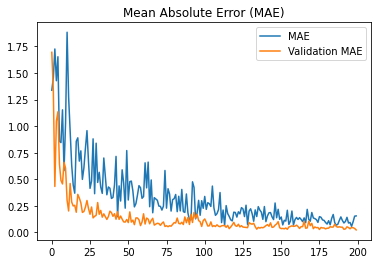

I trained the model using Mean Absolute Error (MAE) as loss, and Adam as an optimizer. Training itself posed no real troubles, but if I were to change something, I might have opted for a static validation dataset rather than one that is randomly generated. Having the validation dataset dynamic did not ruin its purpose, but likely made it a bit more inconsistent.

Depicted below is the progression of the MAE throughout training.

Predictions

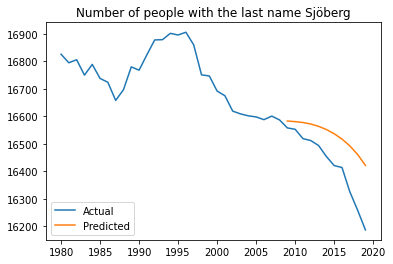

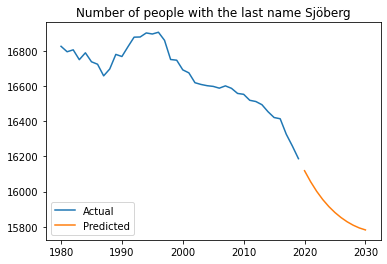

Although the dataset was not very large, I was able to get predictions that I thought was decent. Depicted below are a comparison of graph of actual versus inferred number of occurences of the last name Sjöberg, and a prediction of the future for the last name Sjöberg.

Problems

One problem that puzzled me for a bit was why the network sometimes would make very suspicious predictions that went in the opposite direction of the trend. It turns out that when the model was making predictions, the magnitude of the output sequence was sometimes slightly off (this was noticeable because the model is sequence to sequence, overlapping on all but one value). This means that, for instance, the network could be noticing and predicting a downward trend; but when you would take the last value of the output and compare it to the input data, it could look like an upward trend (because of the difference in magnitude between input and output sequence). To solve this, I based the predictions on the difference between the last and second to last value in the output sequence, rather than just the last value.

Personal outcomes

- I got to try out Jupyter notebooks.

- Working on the project made me more comfortable with the basic machine learning development process.

- I had the opportunity to write my own data generator, which made me unexpectedly excited.

Project code

The code for this project can be found here.